.

The German School through the ages

by Carolina Marinkovic, Christian Mendoza and Mario Reinhard

Today, the German School “Mariscal Braun” is a school of encounter where both Bolivian and German traditions are lived. It received its present name on 5th October 1942, after Bolivia’s declaration of war on Germany, in honour of the German Marshal Otto Philipp Braun, who once fought for Bolivian independence.

Today the school is open to everyone, regardless of religion or nationality. Discrimination and bullying are not tolerated. Unfortunately, this was not always the case….

While the school was cosmopolitan and tolerant in the 1920s (opening on 9 May 1923) – lessons at the school began with a total of 77 pupils, 43 of whom were Bolivians or “mixed children” with Spanish as their mother tongue, 27 Germans, 7 from other countries – this unfortunately changes just as it does in Germany as a whole. The number of foreign and Jewish pupils decreased or they were listed in the statistics as German and Catholic. Perhaps this is not surprising given the changes in Germany. After all, the school received, then and now, a great deal of support from Germany, both in terms of personnel and finances.

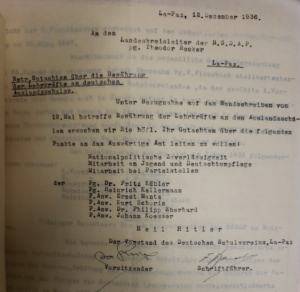

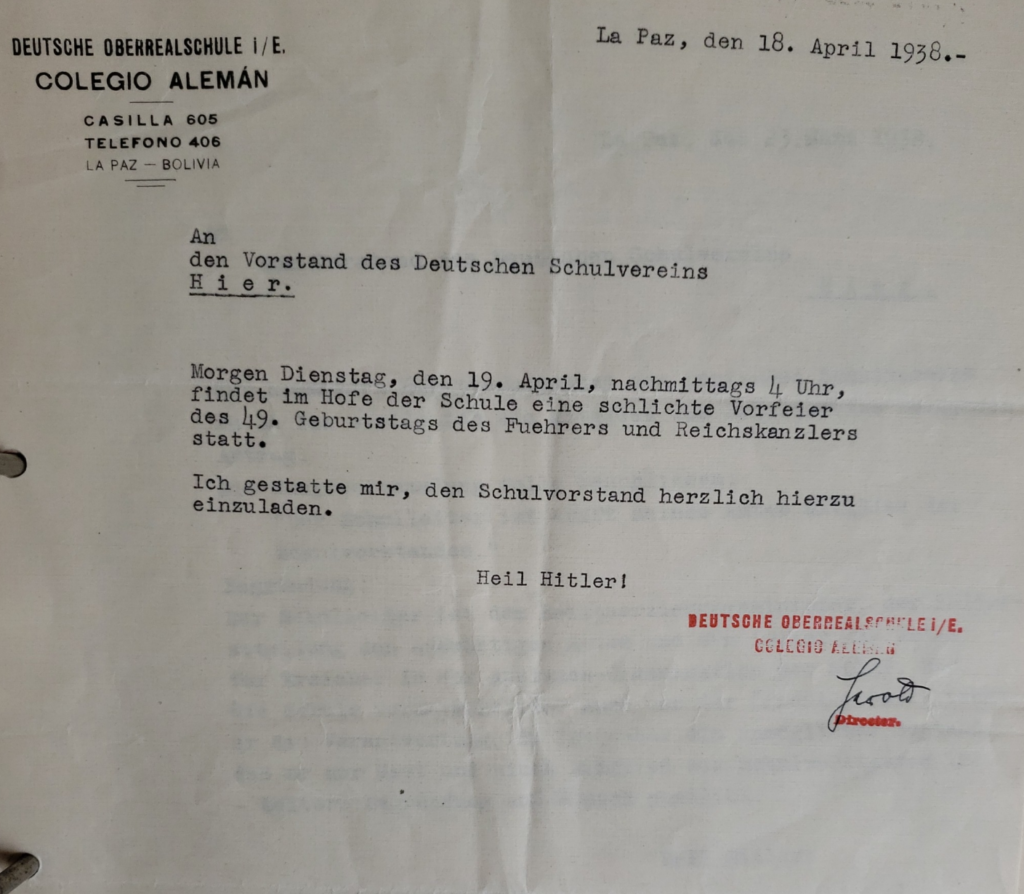

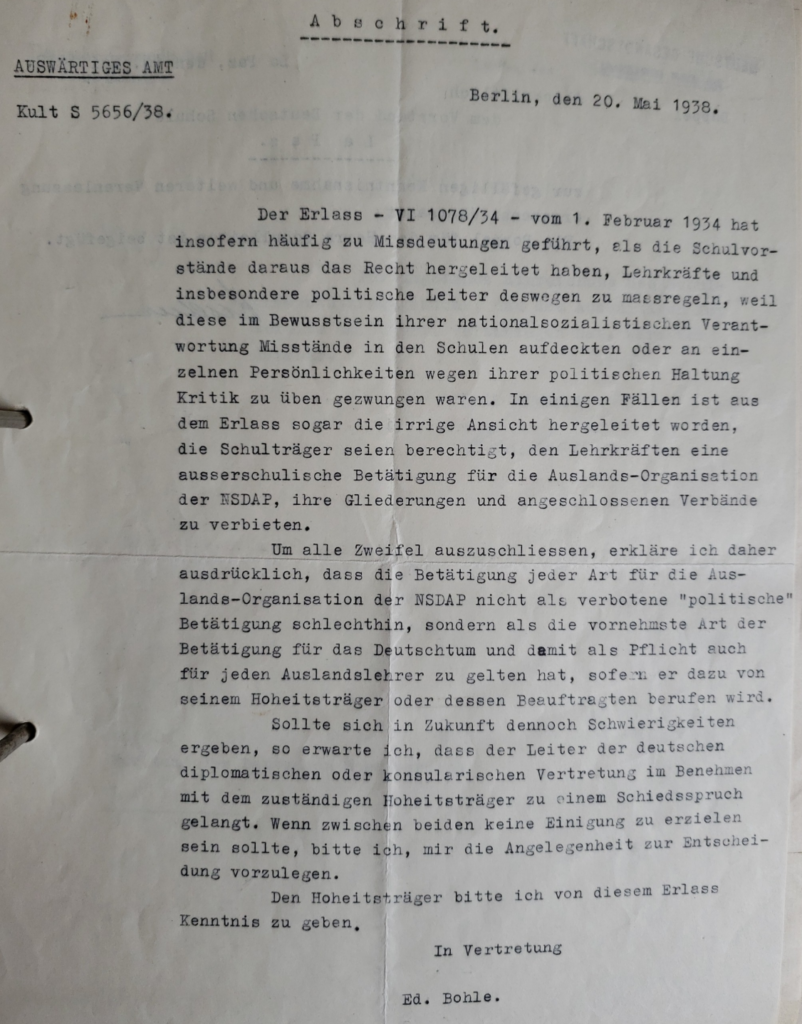

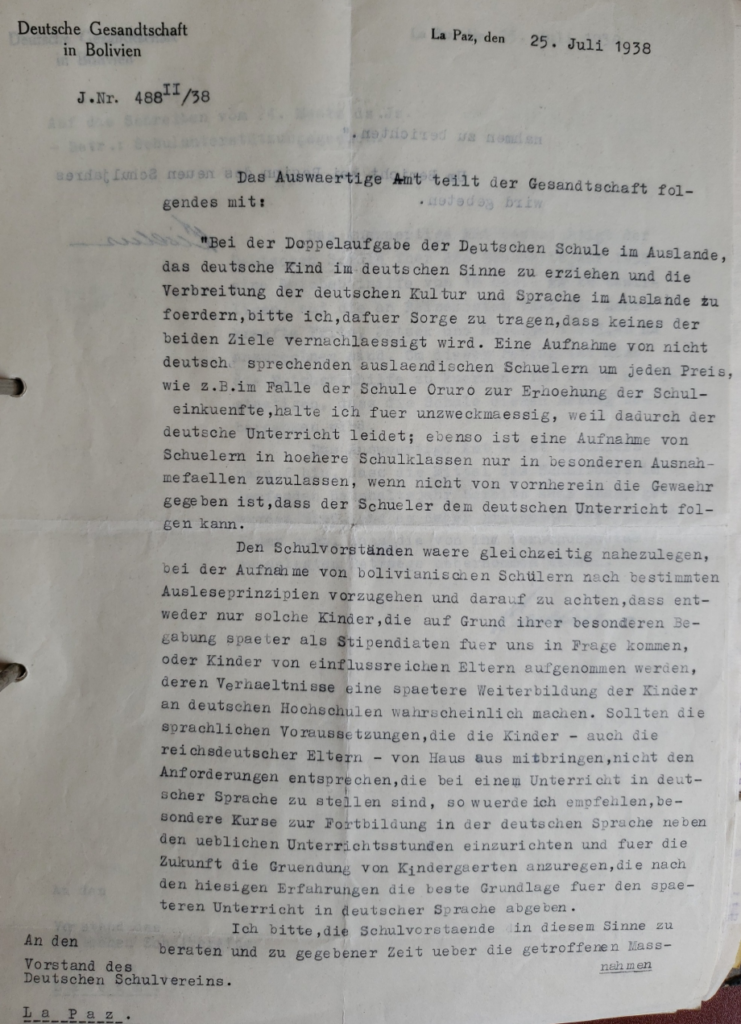

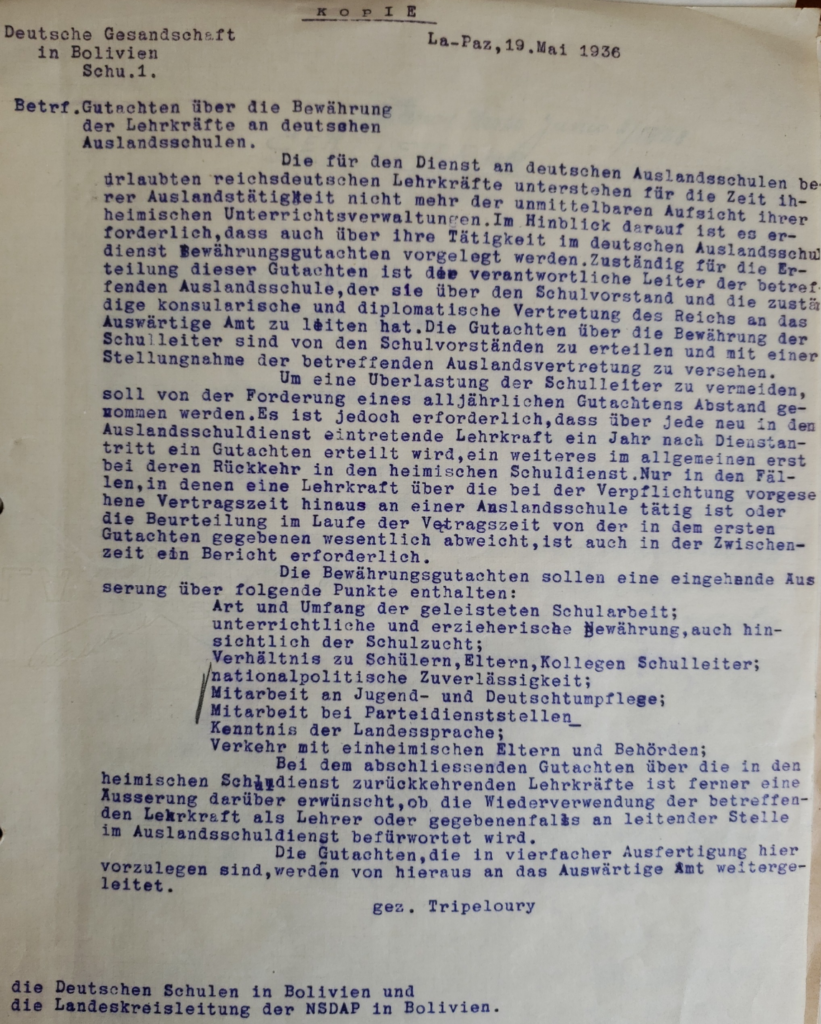

For the 1930s and up to Bolivia’s declaration of war on Germany in 1942, this meant, on the one hand, that sport and discipline were written in capital letters, that teachers were regularly trained and assessed in terms of national policy, that curricula had to meet the National Socialist requirements, but on the other hand that Nazi Germany co-financed the new school building in the Avenida Arce to a considerable extent.

Formalities and content of the staff report

The extent to which school life and teaching was influenced by National Socialist ideology – such as the cult of the Führer, nationalism, racism or expansionism – is also shown by the sources in Chapter 3 or the excerpt from the inventory list of the school library.

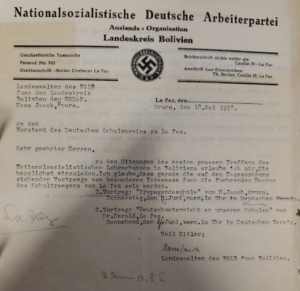

As already mentioned, the German School was not alone in this; the same ideology can also be found in the cultural community as a whole, which held its national-political events at the school (May 1st celebration, honouring Hindenburg and others) and naturally invited the teaching staff, and vice versa, the school also invited the cultural community.

The school and the cultural community, the latter being at the same time the school owner, are closely connected, both in terms of personnel and content, and the commitment to the NSDAP was explicitly demanded by Germany.

In 1924 the school had 101 pupils. The number of Bolivian pupils had risen to 58, but the number of German pupils remained at 27. In addition, there were now 18 German-speaking Bolivians. The school gradually became more international, with three US-Americans and a total of eight English-speaking pupils. In that year, the German School also received its first Jewish student, Louise Kavlin from Vilnius, Russia (today Lithuania). Later her brothers followed her to DS La Paz, where the family remained until 1939.

In 1932, the number of pupils increased to 412. But it is amazing how drastically the number of those with Bolivian citizenship decreased within two years: from 340 to 285. In contrast, the number of German students had doubled within two years, from 43 to 87. Nevertheless, there were more and more Bolivians than Germans at the DS La Paz, a fact that was not necessarily welcomed in Germany.

However, the number of German-speaking Bolivians remained at zero for the time being. This is because this year, the German-speaking Bolivians were registered as Germans. This explains the decline in the number of Bolivian pupils and the marked increase in the number of Germans at German schools. At the same time, the school became more international, with 40 foreign pupils, including Argentinians, Chileans, Peruvians, Cubans, Mexicans, Americans, English, Italians and Swiss.

In 1941 the world war was in its third year. The number of Bolivians registered at the school was 416, 9 of whom spoke German. The number of German students rose to 81 because Bolivian families were again registered as German families. The number of students from other countries dropped to 12. Due to the war situation, no American, English, Russian or Mexican students were registered at the school anymore. Due to the friendship between Germany and Japan, however, there are now a total of four Japanese pupils at the school. By the end of the war their number had increased to six pupils.

In the following year, there were many Bolivians and only a few Germans, because the Bolivians who were still considered Germans a year ago were considered Bolivians, probably not least because Bolivia entered the war on the side of the Allies. Pupils from the “allied” as well as from other European countries did not attend the German School until the end of the war, except from neutral countries such as Switzerland.

In 1945 the number of Germans was 40 (5%), while the number of Bolivians was 690 (93%) – out of a total of 746 pupils.

Even though there was a constant shortage of teachers due to the consequences of the war in the 1950s and 1960s, the school continued to develop, became an experimental school and grew continuously. After the war, between 1946 and 1951, the German School was very well established, had more and more pupils, in 1951 a total of 1114. The number of students of other nationalities also increased again. They came from a wide variety of countries, including the Netherlands, Uruguay, Paraguay and Chile.

As a result of the school agreement between the Bolivian and German states, the German School is relatively free in its internal organisation and the pupils can acquire the school-leaving certificates of both countries.